Put aside the X’s & O’s. This year’s NHLCA Global Coaches’ Clinic added a new kind of play to the board. In a dynamic workshop that traded whistles for real-world role-play, coaches got hands-on training in negotiation, learning how to advocate for themselves, navigate high-stakes conversations, and strengthen their leadership toolkit on and off the ice.

By Scott Burnside

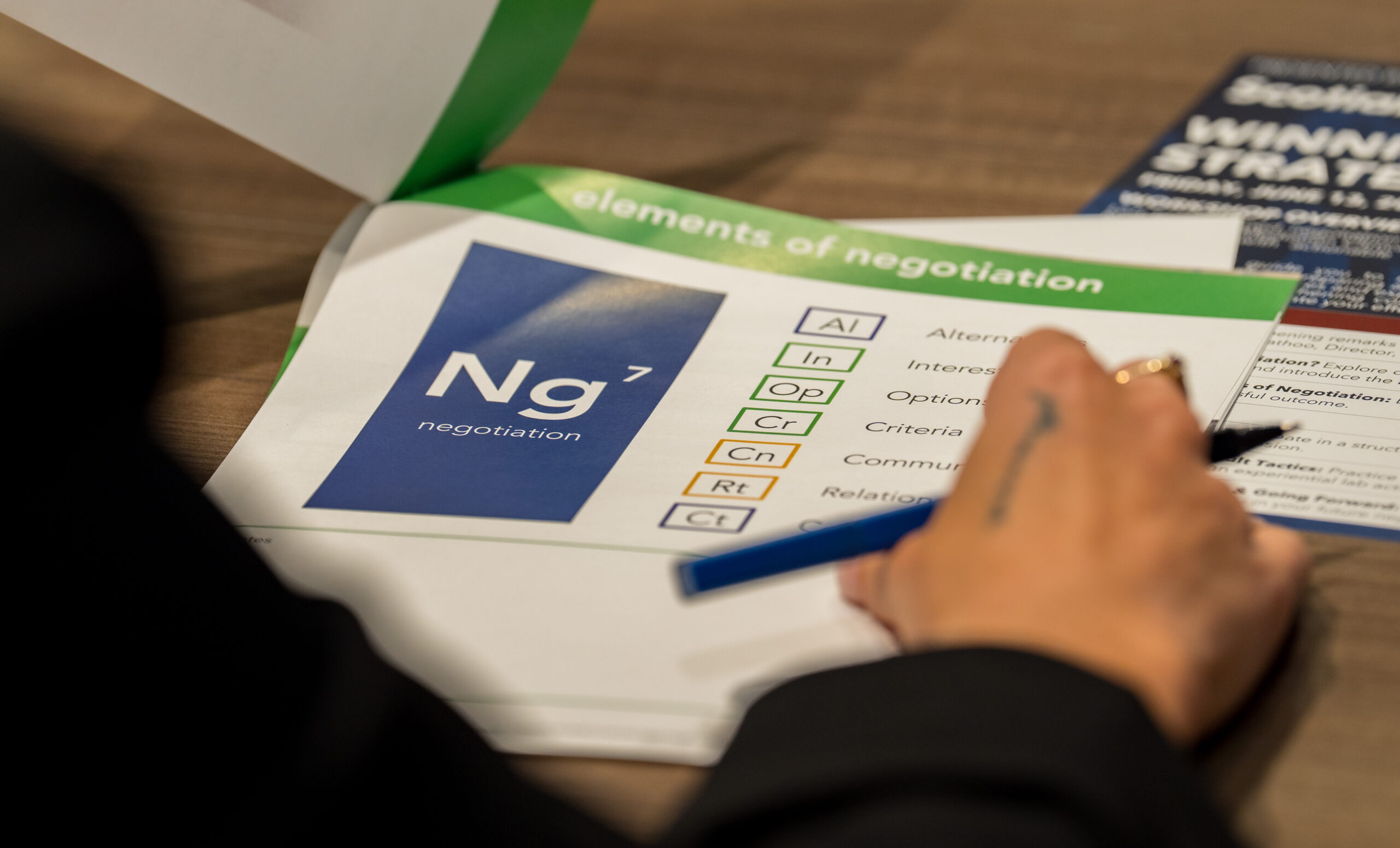

Lisa Dicker’s session on negotiating starts with participants getting into an arm-wrestling position with a partner.

Interesting, no?

It’s a reminder to the members of the National Hockey League Coaches’ Association in attendance that this isn’t going to be a simple exercise in how to ask for more money.

And that’s really the whole point of Dicker’s unique session held recently at the annual NHLCA Global Coaches’ Clinic in downtown Toronto.

We’ll get back to arm wrestling shortly, but first a little background.

Dicker is not a hockey person per se. She’s from Tennessee and is understandably more familiar with University of Tennessee sports lore than National Hockey League lore. But whatever knowledge deficit she might have when it comes to sticks and pucks, Dicker more than makes up for in her understanding of the pivotal areas of negotiation. Dicker is a graduate of Harvard Law School and is a Clinical Instructor with the Harvard Negotiation & Mediation Clinical Program. She has worked with a global pro bono law firm advising on peace negotiations and conflict prevention including participation in the Sudanese Peace Talks and the United Nations-led Intra-Syrian Peace Process as well as peace building efforts in Yemen and working to deal with violent extremism in Tanzania, according to the Harvard Law School web site.

Photo: Lisa Dicker, Consultant at Triad Consulting Group; Clinical Instructor with Harvard Negotiation & Mediation Clinical Program

Lindsay Pennal, the Executive Director of the NHLCA, met Dicker at a Women in Sports and Events (WISE) gathering in Toronto just over a year ago where Dicker led a similar discussion on negotiations.

The NHLCA has been able to tap into funding through the NHL/National Hockey League Players’ Association Industry Growth Fund and Pennal felt Dicker’s negotiating program would be a great fit for coaches attending the Association’s annual summit, especially the men and women in the Association’s Female and BIPOC Coaches Programs. Thanks to the IGF funding, as well as contributions from the Scotiabank Women Initiative and Canadian Tire, Dicker’s program was offered to attendees free of charge.

“The negotiation workshop is an important initiative because coaches are constantly navigating complex interpersonal dynamics, but formal negotiation training is rarely accessible to hockey coaches,” Pennal said. “The gap is even wider for women and BIPOC coaches who, historically, haven’t had equitable access to funding or leadership development opportunities.”

“Seeing our NHL coaches role play tough negotiation tactics with the women and men from our diversity programs was a highlight,” Pennal added.

As the session wound down to one-on-one role playing at the end, the din in the room made it clear participants were buying into the give and take of applying the skills outlined by Dicker during the workshop.

“I think that there are certain skills and frameworks that I use across a variety of professions. But I always want to have a conversation with the client contact, so in this case, Lindsay, to be like, what’s trickiest for your audience, typically? What types of negotiations do they most often have and where are areas where you see folks often get tripped up or come to you for advice and suggestions?” Dicker explained in a post-session interview.

For many of the attendees, the thought of sitting down with a team owner or general manager to negotiate a new contract or work relationship can be harrowing. The long-standing concept that no one person is above the team sometimes runs counter to speaking up for yourself and touting your own skills and importance to the team.

Certainly, among the participants, that was a common fear or apprehension that many noted during Dicker’s program, attended by roughly 75 people. The group included 30 members of the NHLCA’s Female and BIPOC programs, 25 NHL and American Hockey League coaches, and 20 corporate partners from the NHL and event sponsors Scotiabank and Canadian Tire.

Photo: Christian Hmura, Skills Coach, New York Rangers (left), Sergei Brylin, Assistant Coach, New Jersey Devils (centre) and Vanessa Hettinger, Skating Coach (right).

The three-hour workshop helped break down the layers of negotiating and how best to prepare yourself for whatever form an individual’s negotiating experience is going to take. Dicker noted that even though hockey’s culture may seem to preclude pumping your own tires, she insisted that’s exactly why it’s important men and women give voice to their own skills and positive qualities.

“It is actually an overall benefit to the team for you to negotiate strongly for your interests,” Dicker wrote in a note following the exercise. “For example, if you need more resources to perform your role better, that will ultimately benefit the team. Or, if to have longevity in your position, you need additional pay and better vacation days to rest and recover, your growth and progress in the position over time is a benefit to the team. Or, if you will simply be able to focus better on the substance of your coaching if your office space is more organized, then asserting with your colleague about a neat, shared desk is a benefit to the team.”

“Reframing negotiations in your mind from a “win-lose” problem to a value-creating exercise that can benefit all parties involved is particularly helpful in team-first cultures. You are part of that team and your ability to thrive is key to team success,” Dicker added.

Among the many layers that go into negotiation, perhaps one that resonated most clearly with the coaches in attendance, was the formulation of a backup plan or BATNA (Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement).

Having a Plan B or fallback plan – and more importantly, understanding the strength of that plan – will often dictate how to approach the main point of negotiation. For instance, if you’re a skills coach looking for a position with a team and have other teams that have expressed an interest in your specific skill set, that changes the negotiation dynamic with your preferred team compared to having a less robust BATNA.

All of the strategies for successful negotiation – and what to do when the negotiations go sideways – hold true for all kinds of interactions, not just as it relates to a job and compensation for said job.

Photo: NHL Coaches’ Association

Life is full of negotiations that may not seem on the surface to be negotiations. If a player is angry about ice time or wants a trade, those discussions are by their very nature forms of negotiation.

Even something as simple as planning where to go for dinner or sitting next to someone in an office where space is shared means coming to a mutual agreement.

“I think that it can really kind of hamstring folks in negotiations if you only think of it as this annual big contract negotiation as opposed to a skill that you are constantly practicing,” Dicker said. “And some of the skills work well for you, and some of them don’t. You may be really great about talking about how we’re sharing the desk in the office that were both somehow seated at and have paperwork everywhere. And that may be something that you’re really good at. But at the same time, if a player is starting to talk about a trade or their ice time, that may be something that gets your hackles up more. What’s different about those? How do I improve on them? And then also, how does that play into my bigger, more formal contract negotiations as well?”

The reality is that for every participant, the takeaways from Dicker’s presentation will be different.

Cathy Andrade is a former pro figure skater turned skating instructor who has been an institution in the hockey skills world in the San Francisco Bay Area since 1992. She has worked with a variety of NHL players, including Joe Pavelski, and recently completed her first season working with the San Jose Sharks as a skating consultant.

She found the negotiation session eye-opening. “It got my mind going. Because I’m like, well, you’re in it now, right?” Andrade said.

“These are skills I’ve never used and I’ve never really had a formal job interview to this point and always had my own company, and so even at my age I’m in new territory, so it’s great to learn.”

“I’m here. I need to learn,” Adande added. “I thought [Dicker] did an amazing job. I thought the thought-provoking material was pretty impressive.”

Photo: Dennis Ruppe, Manager of Hockey Operations, Hockey in New Jersey.

Dennis Ruppe, 27, wasn’t even sure he was going to attend the negotiation session because he didn’t know whether it would apply to him in his role as Hockey in New Jersey’s Manager of Hockey Operations and an aspiring coach.

But by the end of the session, he was sold on Dicker’s process.

“I wasn’t sure if I was going to do it originally, just because I was not negotiating that often. But then the way she framed it, you’re actually negotiating all the time,” Ruppe said.

“You think about, oh, you’re walking to a contract negotiation or something, some of these big things, but she made the example that it’s like, who’s going to go through the door first? It was really, really interesting,” Ruppe said.

Big picture, the introduction of a program like Dicker’s negotiation session speaks to the NHLCA’s mandate to push the envelope on learning and development for coaches at all levels and from all backgrounds.

Laurie Kepron, Senior Vice President of Partnership Marketing, has been with the NHL for 29 years and introduced Pennal to Dicker at last spring’s negotiating workshop in Toronto; she felt Dicker’s workshop would be a perfect fit given Pennal’s vision for continued educational growth for members of the NHLCA.

“I’ve known Lindsay a long time, since she really started with the Coaches’ Association. And it’s been just so exciting to see the development of that particular group and the coaches and the programs that they’ve put in place,” Kepron said. “And certainly, as part of the NHL family, they play a very significant role.”

Photo: André Tourigny, Head Coach, Utah Mammoth, takes part in the NHLCA Negotiation workshop.

In particular, Kepron praised the NHLCA’s ability to put “real tools in place and really working to create that community at all levels, not just at the NHL level.”

“I think it’s so important because I think our game is so much more than just what’s on the ice,” Kepron added. “Our game is a game of people at its foundation, and it’s a game of leadership and community. So, bringing opportunities to share in all of that together just makes all of us better. And I think fundamentally, what we all are interested in is the standard of excellence and how do we raise each other up.”

Ah yes, the arm wrestling that started the whole session rolling.

The instructions were simple. Assume the standard arm-wrestling position. Participants would be awarded a point every time they brought their partner’s arm to the table. But – and this was key – Dicker noted there was no punishment for having your arm taken down.

Still, for most people, the natural reaction was to oppose your partner and hold firm. Not for veteran NHL coaches Bob Woods and John Stevens. They offered each other no resistance, and so their arms were flopping back and forth.

When Dicker asked how many points participants had accumulated, most reported a small number. But Stevens and Woods reported numbers in the high 20s, suggesting they had come to an unspoken understanding, or negotiation, on how they would perform the activity.

Photo: John Stevens, Assistant Coach, Vegas Golden Knights (left) and Bob Woods, former Seattle Kraken Assistant Coach (right).

Scott Burnside is an award-winning journalist who received the Elmer Ferguson Award from the Hockey Hall of Fame in 2024. He’s covered the NHL and international hockey for over 35 years.

Recent Comments