By Scott Burnside

The pinch-me moments when you’re organizing a revolution can come in many forms and in many sizes.

When you’re in the midst of revolutionizing opportunities for hockey coaches who have historically faced barriers to accessing top-level coaching jobs, those pinch-me moments can come on the biggest of hockey stages and they can come in the form of an excited phone call about an unexpected job offer.

Each such moment is vital to the process and Lindsay Pennal, Executive Director of the National Hockey League Coaches’ Association (NHLCA), keeps an email file of such moments on her computer, it’s called simply ‘good stuff’.

“And there’s been dozens of pinch-me moments. It’s just really exciting to see. I know there’s more to come,” Pennal said.

The big moments are easy to identify and they serve as a kind of beacon for the dozens of men and women who have become part of the NHLCA’s multi-pronged coaching development programs, specifically the NHLCA BIPOC Coaches Program and the NHLCA Female Coaches Program.

Let’s start with an easy one from the ‘good stuff’ file – Jessica Campbell because Jessica Campbell illustrates so clearly what success looks like to the rest of the hockey world.

The three pillars of the NHLCA’s broad efforts to increase opportunities for women and BIPOC (Black, indigenous and people of color) coaches are networking, professional development and visibility.

Campbell has parlayed all three elements, plus a relentless drive to become better at her craft, into a gig with the NHL’s Seattle Kraken where she is an assistant coach. She is the first female to hold such a role in NHL history.

Photo: Kevin Clark / The Seattle Times

Campbell’s presence on a nightly basis behind the Kraken bench serves as a constant reminder of what is possible when skilled, driven hockey people have the opportunity to display those qualities.

Her groundbreaking rise through the pro coaching ranks has made Campbell something of a ‘star’, a status she did not seek but which she has nonetheless embraced.

“I think that it’s really important for me to continue to share that experience, especially with other women and female coaches. Because you can network all you want, you can connect with people, but you’ve got to get to doing the work and you’ve got to get in the trenches,” said Campbell a native of the small prairie town of Rocanville, Saskatchewan.

Campbell had already established herself as a high-end skills practitioner working with multiple NHLers when she reached out to Pennal about joining the Female Coaches Program in early 2021.

Her experiences with the program, chatting with men who would soon be her peers, reinforced Campbell’s belief in her own skills and her own ability to take on bigger and bigger challenges.

She recalls specifically a conversation with long-time NHLer, a rising coaching star, Marco Sturm, mostly about skill development and his experiences as a young coach.

“And just to ask him a lot of questions around his approach and his experience and how the players operated at that level on a team setting in-season,” Campbell recalled. “And I was hands-on doing skill development with NHL players at that time too. So, it was really important for me to ask those questions and to ask someone who was doing it and also offering the remarks back in a setting where he was there also to help and to teach me or to teach the group.”

“So, that moment was definitely memorable for me because I don’t think I would really have had the opportunity to connect with Marco that way had I not been part of the group,” Campbell added.

Campbell broke barriers when Dan Bylsma brought her on to his staff with Coachella Valley of the American Hockey League. Bylsma then added Campbell to his staff last summer when he took over as Kraken head coach.

That Campbell was part of the NHLCA’s Female Coaches Program isn’t the reason she’s an assistant coach with an NHL club. But there’s no denying the program was a catalyst in exposing potential employers to Campbell’s impressive skill set that might not otherwise have been aware of her presence in the game.

Kim Davis (left), NHL Senior Executive Vice President of Social Impact, Growth Initiatives and Legislative Affairs, with Jessica Campbell (right), Assistant Coach, Seattle Kraken during the 2022 NHLCA Global Coaches’ Clinic in Montreal, Canada.

“Sometimes you need an opportunity to get to do the work, but you also need to be able to put yourself in a position to learn and to prepare to get those jobs and to earn those jobs,” Campbell said.

Big picture, the more people like Campbell get opportunities and seize those opportunities the better the game becomes.

“Because, if you don’t build better coaches, if you don’t connect good people and passionate people and create a space for people to come into the game, then how do you get better?” Campbell asked. “How do you grow? How do you expand and learn? And so I think that with more time, with more resources the program is only going to continue to be better and better.”

Suffice it to say that Campbell’s career arc figures prominently in Pennal’s ‘good stuff’ file.

If you’ve never heard of Pennal before that’s probably not surprising. She has never coached a game of anything. She’s not a hockey person, per se. Or at least she wasn’t.

That started to change almost a decade ago when long-time business associate Michael Hirshfeld asked Pennal to act as a reference for a job he was hoping to get as the head of the NHLCA.

Hirshfeld got the job and immediately asked Pennal to do some consulting.

Pennal joined the NHLCA full-time in 2018 and she and Hirshfeld reshaped the NHLCA on a number of fronts including introducing a remote mentorship program that was followed by two ground-breaking programs that put female and BIPOC coaches in direct contact with NHL teams and coaches for one-on-one immersion sessions.

Hirshfeld is now the GM of the Ottawa Charge of the PWHL and Pennal has taken over as Executive Director of the NHLCA.

There is a kind of domino effect to all of this, each domino pushing over an even larger domino in terms of creating educational and growth experiences for coaches throughout the hockey world.

The NHLCA joined the NHL in Europe hosting coaching clinics when NHL teams were playing games outside North America.

Later, there would be a remote NHLCA Mentorship Program that would be open to coaches from around the world.

The NHLCA also began pairing NHL coaches with hockey leagues and organizations in North America. For instance, successful NCAA coach David Quinn did a webinar with NCAA coaches and so on.

It was at the draft in Vancouver in 2019, though, that the reality of the coaching landscape smacked Pennal right in the nose.

2019 NHLCA Global Coaches’ Clinic in Vancouver, Canada.

As Pennal looked out at the several hundred coaches in attendance, she saw a crowd that was overwhelmingly white and male. Did this mean there were no women and/or people of color who wanted to coach hockey? Of course not.

A few months later, on International Women’s Day in March of 2020, the NHLCA announced their Female Coaches Program that would address issues of accessibility and education for female coaches, mostly at the NCAA level to start, who wanted to be better coaches; not just better coaches of girls and women, but better hockey coaches.

The BIPOC Coaches Program would follow in June of 2020, two programs with the same structures and goals.

“Little did we know the world was going to be shut down by a pandemic,” Pennal recalled with a laugh.

The initial plan was for 50 women in the program to gather periodically in-person with NHL coaches starting at what would have been the 2020 NHL Draft in Montreal. But the pandemic suspended the draft and forced Pennal and the NHLCA to pivot quickly.

“We were like, why don’t we start now? We have 200 NHL coaches just sitting at home, desperate to talk hockey,” Pennal recalled.

The NHLCA set up remote chats pairing female coaches with NHL coaches to talk about specific elements of coaching from dressing room culture to power play structure to practice planning and so on.

The women would present first and their NHL counterparts would respond a week or so later. Members of the larger group could ask questions. It was a roaring success.

In just over a month there were 25 remote collaborations as members of NHL coaching staffs stepped up without hesitation.

“It was incredible,” Pennal said. “Our NHL coaches completely stepped up. It was ‘What do you need? How long do you need? What time?’ Coaches love coaching and they want to talk hockey and they want to talk to other coaches. We set up the forum to facilitate this during an otherwise isolating time.”

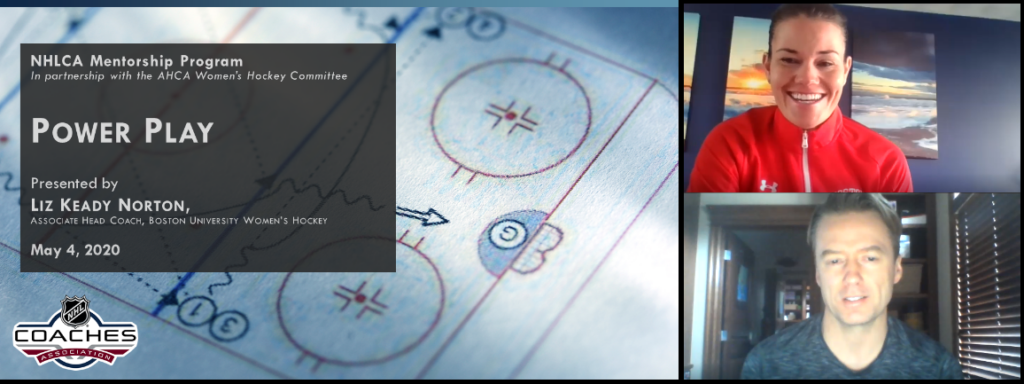

Photo: Glen Gulutzan, Assistant Coach of the Edmonton Oilers, discusses power play strategies alongside NHLCA Female Coaches Program member, Elizabeth Keady Norton.

These types of virtual coaching seminars went on for women and BIPOC coaches throughout the pandemic. Then, as the restrictions eased, the NHLCA moved into a new phase of expanding both the female and BIPOC programs.

Pennal spoke to NHL GMs and explained what the NHLCA had been doing and how she needed them to open the doors for in-person job shadowing for members of the programs.

In the fall of 2021 Duante’ Abercrombie and Nathaniel Brooks were invited to assist at the Arizona Coyotes development camp.

[Here is a link to a fine documentary by filmmaker Kwame Damon Mason on the coaches’ experience with the Coyotes: https://youtu.be/xhIBUItKLRA]

What began with one team became five teams, became 15 teams, and now 17, each offering in-person experiences at development camp, training camp and in-season visits and communications.

Last fall the in-person experiences expanded to include two American Hockey League teams and mentorship opportunities were created for the American Hockey League All-Star event.

A stellar collegiate and professional player Kori Cheverie moved seamlessly into coaching when she became the first female head coach of a Canadian men’s university team – what is now known as Toronto Metropolitan University.

She coached and did skills training in minor hockey associations in the Toronto area.

Then, one day, she found herself on the ice at the Pittsburgh Penguins practice facility drawing up a training camp drill for Sidney Crosby, Evgeni Malkin and Kris Letang and the rest of the Penguins.

Photo: Pittsburgh Penguins

“I was up there drawing on the board with Sid and Kris (Letang) and Evgeni just on one knee watching me draw the drill and I was like ‘what life am I living right now where this is happening?” Cheverie recalled with a laugh.

The simple answer to that rhetorical question is that these dream-like moments become reality because someone puts in the work and when the door opens, they step up because they can.

“I just knew when I was going into that environment it was time to get to work, whatever they asked me to do I was going to do,” said Cheverie who is currently the head coach of the PWHL’s Montreal Victoire.

Pittsburgh Penguins head coach Mike Sullivan is a two-time Stanley Cup champion and one of the most successful U.S.-born coaches in the history of the game.

It would be easier for a person with Sullivan’s resume to say, ‘no thanks, I’m too busy,’ when the NHLCA comes calling.

That is not Sullivan’s way nor is it the way of virtually every coach from NHL head coaches on through assistants, associates, goaltending and video coaches, who have been tabbed by Pennal to help out with the mentorship programs.

“I think one of the best parts of our job, given the position we’re in, is our ability to give back. I think it’s our responsibility to give back,” Sullivan said recently. “If we can help the next generation of young coaches grow and develop their skill sets so that they have the opportunity to chase their goals and dreams like we’ve been able to do, for me it’s a great thrill.”

The in-person part of the mentorship programs was a natural next step for the NHLCA but it also came with a whole range of questions and challenges, mostly notably, what does in-person coaching look like?

In the end it wasn’t that complicated at all. When Cheverie arrived in Pittsburgh she became part of the staff.

“She skated, she was on the ice during our training camp, she ran drills, she sat in meetings with the coaches and the team. We had her behind the bench during exhibition games. We really tried to include her in every aspect of what we do and how we do it because I felt that there’s no better way to try to impart knowledge or experience than allowing them to live it,” Sullivan said.

Photo: Pittsburgh Penguins

Sullivan recalled asking Cheverie if she wanted to lead some drills at training camp.

“With no hesitation, she said, ‘I’d be happy to do it,’” Sullivan said. “As you can only imagine when you have players of the stature that we have in our room with Sidney Crosby, Evgeni Malkin, and Kris Letang, we have first-ballot Hall of Famers that are on this team, here’s a young coach, a female, that gets up in front of these guys, just how articulate she was and the way she drew up the drill and explained the drill to the guys. I think she instantly commanded a certain level of respect from the players.”

When it works there is something symbiotic about these relationships, a dynamic where the learning is on both sides of the equation and the interaction continues long after the formal part of the program has ended.

For instance, Sullivan spoke to Cheverie’s team when they were in Pittsburgh for a neutral site PWHL game.

“She’s a bright young coach. She’s really smart,” Sullivan said of Cheverie. “She challenged us with thoughts and ideas in some of the meetings, which I think was really cool from our standpoint. She got to share her experience of what she’s gone through with women’s hockey and things of that nature. Now it’s fun to just watch her from afar and watch her run her own team.”

Lennie Childs was the first Black coach of a USHL team and was part of the in-person NHLCA BIPOC Coaches Program with the Seattle Kraken.

Childs was recently named head coach and GM of the Janesville Jets of the North American Hockey League (NAHL). While an assistant at Union College of the Division I ECAC, Childs had introduced a new penalty kill structure and things weren’t going great.

He started looking at NHL teams that had done something similar and was drawn to what the Penguins were doing in Pittsburgh.

“I was like, man, this is, this is a good system,” Childs said. “So, I reached out to Lindsay, and I was like, ‘hey, Lindsay, is there any chance you could get me the email for Mike Vellucci who runs the penalty kill unit? And she was like, ‘yeah, no worries.’”

Vellucci called Childs and the two talked PK systems.

Later, when Childs was in Pittsburgh for a development gathering, Vellucci invited him out to practice at the Penguins’ facility.

“That amazing opportunity that Lindsay really set up has morphed into a friendship with me and Mike now over the last couple of years,” Childs said.

“It really shows the best part of our game, that people do want to help,” Childs added. “No one’s really a closed book, right?”

Photo: Seattle Kraken

Over the past three years, over 20 men and women who were part of the NHLCA’s mentorship programs got new jobs or promotions in the hockey world.

Membership in the Female and BIPOC programs has jumped more than 100% from 80 to more than 170 in less than five seasons.

How long until there’s a female head coach at the NHL level? Or more people of color? It seems inevitable. But this isn’t just about the jobs, it’s about preparing people for a different future than maybe they could have imagined just a few years ago.

Remember the ‘feel good’ file on Pennal’s computer?

One day she got a call from a female coach from British Columbia.

She told Pennal she’d applied for a job as the administrator of a male hockey program in a British Columbia community. And she got it.

She wanted Pennal to know she felt emboldened to apply for the job thanks to her experiences with the NHLCA’s Female Coaches Program and the people she’d met and interacted with through the program.

So, what next?

Glad you asked.

Pennal said many people would be surprised to learn that all of what has been accomplished in the past five years has been done without any budget to speak of.

Lots of sweat equity. Lots of favors being called in.

But the Industry Growth Fund, operated jointly by the NHL and National Hockey League Players’ Association, has seen the value in what the NHLCA is building and now there’s some investment to help expand horizons.

The NHLCA has contracted with a specialist in negotiation from Harvard University to help coaches in what can often be uncomfortable contract negotiation situations and will hold sessions at the NHLCA’s annual conference in Toronto in June. They’ve also partnered with tech companies who help supply specific coaching technology to NHL teams to provide hands-on learning for coaches in their programs.

As a player Kori Cheverie and her peers dreamed of a professional hockey life. Now she’s living that life as a coach of the Montreal Victoire.

If you wanted to, Cheverie said, you could spend every waking hour of every day on your craft as a coach.

“There’s always something that needs to be worked on,” she said. “There are so many different elements to it.”

She couldn’t be happier.

“This is what I do all day. I watch hockey, I coach hockey and strategize. I couldn’t be more fortunate,” she said.

Pinch me.

—–

Scott Burnside is an award-winning journalist who received the Elmer Ferguson Award from the Hockey Hall of Fame in 2024. He’s covered the NHL and international hockey for over 35 years.

Recent Comments